Hello All –

I’m hoping you have a bit of time on your hands because I’ve got a sneaking feeling that this post will be of the long-form variety. In a good way, of course. At least, I hope.

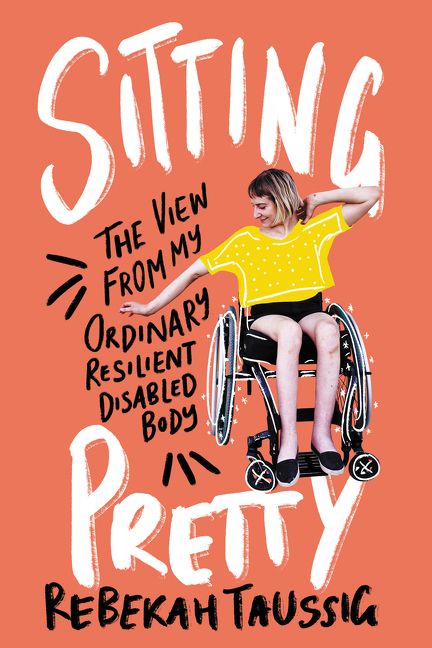

I just zipped through (delightedly, I might add!) the uber thoughtful and insightful Sitting Pretty: The View from My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body by Rebekah Taussig. Though we haven’t actually met in person, her writing, (which I cannot recall how I discovered it) makes me feel as though we are friends. Rebekah writes with an honesty, fierceness, and passion that invokes the same in me, from a perspective similar (we both have beautiful and flawed bodies!) and different – hers ambulates primarily via wheelchair.

Her book examines the ways in which disabled people experience the world and how improving our collective thinking about their bodies and access (my goodness the workarounds of the wheelchair bound!) utlitmately benefits us all.

When I was in college, yakking it up among a group of male friends, a blind woman and her dog approached to ask me where she could find the bathroom. I gave the most succinct directions I could and received the loudest tongue lashing imaginable about her blindness and how dare I expect her to understand. The vitriol parted the group as though the Red Sea, and I shamefully guided her by the elbow along the path I so carefully described.

Decades later, I remain peeved by the interaction, for two reasons. 1. had she clearly communicated with me that she needed my physical guidance, I would have done it. I was and remain that person. 2. More importantly, why wasn’t this something our school provided? The reason for her rage certainly justified, though there is still no excuse for her berating me. I was not about to insult the intelligence of someone without my same abilities.

But now, as I do some foggy math, I wonder, was this in the fall of 1989, my first semester of college and before the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed in 1990 (If you want to see the marvelous story of many of the people instrumental to the legistlation, watch Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution)? Before something as simple as someone guiding a woman to all the necessary (or even frivolous!) places on campus seemed logical? Before the inevitable stress of isolation and an urgent need to pee(!!) in an unfamiliar environment caused her to lash out at me. And after which, whenever I saw her, I immediately shut my trap for fear of it happening again. I mean, really, how simple it all could have been.

That interaction, as it goes with the most painful, taught me some valuable lessons of clarity in communication and how to be truly helpful. In times since, when I encounter someone with a disability, I ask: “I know this isn’t your first rodeo, but if you need help with that door, let me know.” Or others in wheelchairs, shorter than me, or otherwise hindered, “I’m not the tallest person around, but if there’s something you can’t reach, I’m happy to try.”

What is even more important, and what Rebekah emphasizes, is how we can make this a seamless process for everyone. Which reminds me of another woman, who rode her wheelchair, sometimes with a child on her lap, on the busiest of roads in Portland. My initial feeling was of horror and rage. How dare she put herself and a child in danger like that?! A car could easily hit her. Then the realization hit me, after remembering walking those same streets. There were no wheelchair ramps! She, to get from point A to point B, was left with little choice.

So the question remains — How do we make all spaces more accesible to all? Wouldn’t it be great if there were solutions everywhere, without anyone feeling impotent, or forced into dangerous situations, or hoping for some stranger to offer aid?

Rebekah also discusses bodies that don’t appear disabled, like mine when I am severely depressed, or when I lived with the chronic and debilitating pain of endometriosis. The lousy feeling of being other. How my cheerful demeanor, because, despite how awful I felt, life was still good, made doctors and others doubt me, brush me off, act as though it was only an attention grab. “You just need to learn to relax.” (In actuality my insides were ripping apart. Literally.) “Write a list to make you feel happy!” These responses made me fear telling anyone, because they had the solution to my very simple problem (grrrr….), and I was just a weak and defective idiot, unworthy of love or trust.

She also writes about the common fear (one I share) of a job loss that would deprive us of insurance and critical care. The threat of bankruptcy and outrageous premiums for a pre-existing condition laden body.

What might be most striking about Rebekah’s book, is when she encounters people with the belief that a life without disability is the only one worth living. I can say with certainty, based on my own experience, and witnessing that of my cousin, whose genetic disorder has delayed her walking and speech, lives mostly in a world of her making, one in which she scoots and crawls about, shouting and flapping her arms in laughter and raucous joy, is, quite possibly, one of the happiest people I know. I am enriched and enlightened by her, more thoughtful and clear of purpose in her presence. More joyful, too.